Just

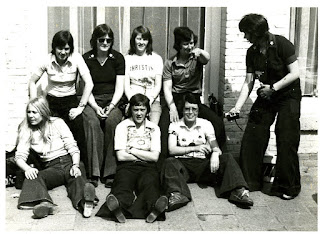

A Ball Game?- Interview with Women’s Football Association’s (WFA) Patricia

Gregory.

Our good friend and former Women’s Football

Association (WFA) Hon. Secretary and Hon. Life Vice- President Patricia Gregory

took some time out to speak to us about the history of the women’s game and

what things were like before Football Association’s (FA) involvement.

Often there is a misconception that until

the last 3-4 decades football has only ever been a male spectator sport, with

the females few and far between turning out to watch matches. However even as

far back as the first ever ‘War Of The Roses’ game in 1870 a significant number

of spectators cheering both Yorkshire and Lancashire sides were female.

Then,

as the popularity of the game increased, women became an integral part of

football crowds.

Well before the FA were formed in 1863 and they took over the regulation

of the modern day sport we know of today, it is documented that women played the

game in a 6-a-side format on Bath’s bowling green as far back as October 1726. Women’s

football is a popular participatory and spectator sport across the globe, but

in England, football’s country of origin, women and girls have been discouraged

from playing the game for many years.This has not always been the case, female football matches are on record from the late 19th century, and, during the First World War female munitions workers and other factory workers, and even some suffragettes famously organised many games for the purpose of raising money for war charities. These were extremely well attended to the extent that at one point the women’s game looked likely to become even more popular than the men’s game.

A couple of years back JBG? founder

Lindsay England and BBC’s Shelley Alexander convinced Patricia to archive the

documents and memorabilia that Patricia had hold of and others belonging to

colleagues for safe keeping and future reference, Thankfully these items are

now with the British Library and the hard work and dedication of these pioneers

of the women’s game can now be examined in those archives.

Looking

ahead to this year’s FIFA Women’s world Cup in France Patricia Gregory says, “It’s over 50 years on since I started a women’s football team, and I am amazed

at the progress of this modern form of the sport which we created in the

mid-1960s.”

Gregory grew up a Tottenham Hotspur

supporter. Watching Spurs’ cup victory

celebrations alongside her dad in the mid 1960s, Patricia began to wonder why it was that women didn't play

football, and then she decided to write a letter, which was subsequently published

in her local newspaper, asking this very question.

In reply, Patricia, who

didn't even play at that time, was inundated with a number of replies and

letters back from young girls/women asking if they could join her team. There

was no team available to play for but the idea of starting one sounded

appealing and a team was formed by Gregory and named White Ribbon.

There

was a stumbling block first off as the team found that because of the Football Association

(FA) ban which had been imposed in 1921, they were therefore partaking in

unaffiliated football matches and they were unable to hire pitches in parks or

from football clubs, or use qualified FA registered referees. The ban had been

stringently applied for 50 years, and the prohibition was only lifted in December

1969.This made it almost impossible to

locate other girls teams so initially the White Ribbon team played young men’s

teams, on their pitches, as this was the only way any females could actively

enjoy the sport.

The

1966 England World Cup win had driven public enthusiasm for all forms of the

game. Using this propulsion, a group of eager and enthusiastic female

footballers along with the help of a number of supportive men decided to form a

women’s game association.

Reminiscing those early years

Gregory says, “Eventually the handful of women’s teams began to organise

leagues and by 1969 the Women’s F.A. came into being and the first ever meeting

took place. It initially started out as the Ladies Football Association of

Great Britain and Northern Ireland. No less than 51 affiliated clubs signed up, 38 were represented at the

inaugural meeting under

the guidance of Arthur Hobbs the first Hon. Secretary. As I could type I was

Hon. Asst. Secretary.”

“In the 25 years of its existence

the WFA really established the sport in England, we created the National Cup

competition (still existing today). We also formed the first official England

team, oversaw a network of nationwide leagues, fought for the registration of

women referees and coaches and much, much more.”

“The FA agreed in 1969 that we could

use referees and also their affiliated grounds. However, The FA were not the

only ones responsible for the alienation of the women’s game at that time. The

Football League (FL, now EFL) didn't lift their objections to our using their

grounds until we played an International match against The Netherlands in

November 1973 (a game played at Reading FC).”

Gregory continued: "The

Union Of European Association Football (UEFA) voted in late 1971 that their

member associations should take control of women's football but they left the

associations to choose how they would control this." “Following on from the UEFA acceptance, on Leap Year Day 1972 The FA recognised the Women’s Football Association (WFA) as the sole governing body of women's football in England at the present time. While most of Europe integrated women's football into their associations, the FA simply recognised the WFA as the sole governing body.”

“The FA formed a Joint Consultative

Committee along with the Women’s Football Association in 1972 and it met in

July of that year for the first time. The very same year the Scots formed the Scottish

Women’s Football Association (SWFA).”

“Arthur Hobbs, stood down at the AGM

in June 1972. He was made an Hon. Life Member of the WFA Council. Sadly

Arthur died in 1975 so never lived to see how much the game progressed to what

we know it is today with a fully professional elite league and players not only

able to earn some sort of a wage, but also supported with a whole team of

backroom staff.”

“Another significant male ally for the

women’s game was David Hunt. He started off as Treasurer of the WFA from the

early 70's and became Chairman in 1977. He was in that position for several

years. He hailed from Buckinghamshire and he became an Hon. Life Vice-President

of the WFA when he stepped down from the Chair. He was with me on the South East

of England League and in 1969 we took a league rep side to the old

Czechoslovakia when the Russians were still in Prague having earlier invaded

the country.”

Recalling more on that first decade

of existence Gregory says, “The WFA office opened at the end of 1980, the

office was initially based in central London but was then relocated to

Manchester in1990.

“In 1984 we saw a new structure for

the WFA with affiliation to The FA on the same basis as a County. Our first

Council representative was the then Chairman, Tim Stearn.”

“In 1992 the WFA had 373 clubs

competing, but that topped 400 very quickly. In that same 92/93 season 151

clubs entered the WFA Cup The WFA then handed the organisation of the game over

to The FA in 1993.”

“The first women's committee was formed

and a women's football coordinator was established at this time. It was called the

Women's Football Alliance, the first meeting took place on 18th July 1993.

“We knew the time was right to hand

it over as we could not afford to keep it going and didn't have the possibility

of raising the sort of money which it needed to take the game to the next level

in all respects handing over in excess of 400 clubs to The FA in 1993 was the

natural progression as we knew that we could not fund the sport in the way it

needed in order to flourish.”

Gregory added: “With no real

financial backing it was always a struggle for the WFA, come 1993, the right

thing to do was to allow The FA to take over responsibility. "We weren't pushing for them to take us over before that because we knew that there wasn't the appetite there - they hadn't embraced the game in the way that, say, the Germans had. But in 1993 we knew we couldn't continue anymore. We'd done all the spadework and they bailed us out."

But Gregory did feel that the FA's "20 years of women's football" celebrations in 2013 ignored those who dedicated their lives to women's football in previous decades.

She wrote a letter to the then outgoing FA chairman David Bernstein, asking him to acknowledge the longer history of the game.

"It's a bit sad and disappointing that what the WFA did for so many years has just disappeared into the ether," she said. "Things evolve and it was probably the right time to stop being involved, but what I find hard to accept is that we are whitewashed out."

“In the 25 years of its existence

the WFA really established the sport in England, we created the National Cup

competition (still existing today), formed the first official England team,

oversaw a network of nationwide leagues, fought for the registration of women

referees and coaches and much, much more.”

“It ‘s a long way women’s football

has come since those early pioneers first kicked a football in 1895!” says

Gregory.

We chatted more with Patricia and

between us followed up leads and research but often this has only resulted in

more questions than answers with very little documentation on female football

ever being taken let alone archived.

Here

are a few more stats and notes of early pioneering days of the women’s game:

It’s possible that women were

playing the game on a regular basis as early as the 1830’s, though the game would have only been

5. 6 and 7-a-side matches.

A picture has been found which depicts

a female game in 1869 and if established as being correctly dated this could

well be one of the first pictures of women playing football.

For some time a game played in an 1895

match at Crouch End, North London was considered to be the earliest official

women’s match in the world which was billed as North v South but then

information surfaced of an earlier set of fixtures claiming similar. Those

being Scotland v England matches in 1881 were reported in the Glasgow Herald.

There were also games in Blackburn, Liverpool and Manchester going under the

title England v Scotland but there is reasonable doubt that they were as billed

an actual international. Early

newspaper reports were not particularly generous on these games, a Manchester Guardian reporter

suggesting the following, “When the novelty has worn off, I do not think

women’s football will attract the crowds”.

A Sketch article of 6th Feb 1895

refers to the ‘British Ladies FC match’ North v South, which seems to be the

North of England reference. Their team had a "custodian", a lady from

Glasgow and the result was 7-1 to the

North. The match lasted 60 minutes and had a crowd of 10,000. The article

finishes "it must be clear to everybody that girls are totally unfitted

for the rough work of the football field".

Information is also unclear as to the

names of some of the players for instance was Nettie J. Honeyball a pseudonym as she wasn't listed on the

1891 census, and was her real name Nellie Hudson as some reports say?

Here's a puzzle. The name Nellie Honeyball in London appears on the 1911,

1901, 1891 and 1881 censuses. Family research isn’t straight forward and often the

problem is names change. She seems the most likely candidate for Nettie. But, there

is also a Harriet Honeyball on the 1901 census living in Camberwell, London but

born in Coggleshall, Essex. Take your pick… was she Nettie, Harriet or Nellie?

The first official international

fixture (and quite possibly the first ever women’s

international in the world) between Scotland v England was played at Greenock

on 18th November 1972. Final

score being Scotland 2 England 3. First blood going the way of the

England side. The return match result was England 8 Scotland 0, a game played

in June 1973 at Nuneaton FC.

The North West’s famous Dick, Kerr’s

Ladies travelled across the channel to play a select French side in 1921 on a

small tour across the country with games taking place in Paris, Roubaix, Le

Havre and Rouen. They had formed a few years

earlier after the suspension of the Football League at the end of the 1914-15

season. A number of

women working in factories began to play informal games of football during

their lunch breaks. At Dick, Kerr & Co, a Preston-based locomotive and

tramcar manufacturer, the female workers showed a particular aptitude for the

game. Watching from a window above the yard where they played an office worker

Alfred Frankland spotted their talent and set about forming a team. The team

was led on the pitch by founding player Grace Sibbert and under Frankland’s

management, they soon drew significant crowds to see their games. They beat

rival factory Arundel Coulthard 4–0 on Christmas Day 1917, with 10,000 watching

at Preston North End’s Deepdale stadium.

Even after the FA ban of 1921 a

number of teams kept playing for some years. In the 1950’s Manchester

Corinthians was the most well known Manchester club. Fodens were around in the

50's too although they came from nearby Crewe.

Sheila Parker, who was the first

England women’s captain (England

1972-1984) said,“ When the FA ban was finally lifted I was

about 24 years old. I was asked to captain England in the first official

Women’s FA match, against Scotland in 1972, which we won 3-2. A little known fact also accompanies the back story of this

fixture in the following context in that the first Scotland v England men's match

was also played in Glasgow exactly 100 years before - a pure coincidence!”

Looking at the players

internationally (i.e. officially playing for England) during the seventies,

eighties and early nineties and finding out ages is also still unclear, which makes

records of youngest ever player and/or goal scorer hard to pinpoint. We have

found documentation of a Linda J. Curl being born in Norwich in the first

quarter of 1962 but can't be absolutely sure she is the England player. Curl

was in the England squad from mid-1976. If the information is correct you could

say Linda was certainly one of the youngest England players at that time if not

thee youngest.

Likewise Jeannie Allott also played

for England. Again, looking up her birth you can find a Jeannie C. Allott being

born in Crewe in the first quarter of 1957. Allott was in the first England

squad in 1972 and is listed as 16 years. If it's the right one she would have

been under 16 in November 1972 when she scored England's third goal, possibly

being one of the youngest scorers of the Lionesses team.

Other notable questions can be asked

about female referees during these mid to late 20th century years. Pat

Dunn, the first Chairman of the WFA, who hailed from Dorset was also one of the

first ever female referees, Pat died in 1999. Joan Briggs is another name which

crops up a few times was a female referee, but again little more is known about

her involvement.

The history of the Women’s FA can be

viewed on the website : https://wfahistory.wordpress.com/